706

Catheter tip position

Poor tip position increases risks of: thrombosis, arrhyth-

mias, perforation of vein wall (causing hydrothorax, cardiac

tamponade, extravasation), catheter failure, pain on injec-

tions, and stenosis. A adequate length of catheter, in long

axis of the SVC, with its tip above the pericardial reflection

is traditionally considered ideal, and this approximates to

the level of the carina. This is often not possible, particu-

larly with left-sided catheters (18). A frequent problem is a

short catheter with its tip abutting vein wall with an acute

angle (Figure 5).

Most practitioners now aim to have catheter tips at the

cavo-atrial junction (two vertebral body units below

carina) (19).

Imaging

Short-term CVCs are usually inserted without real-time

imaging, with a CXR to confirm positioning. Catheter tips

move with changes from lying to sitting/standing, or on

deep breathing (20). ECG guidance or electromagnetic

sensors are increasingly used, but do not confirm either

arterial, venous, and mediastinal placement, or a coiled

tip.

Misplaced catheters

Catheters may be misplaced within the venous system

following an abnormal path to the neck, the arm or across

the midline and need repositioning unless for very short

term use. Alternatively patients may have a normal variant

of anatomy or acquired stenosis of the great veins leading

to misplaced catheters. Catheters are typically easily

recognized in such positions and specialist advice is not

generally required before revision, use or removal.

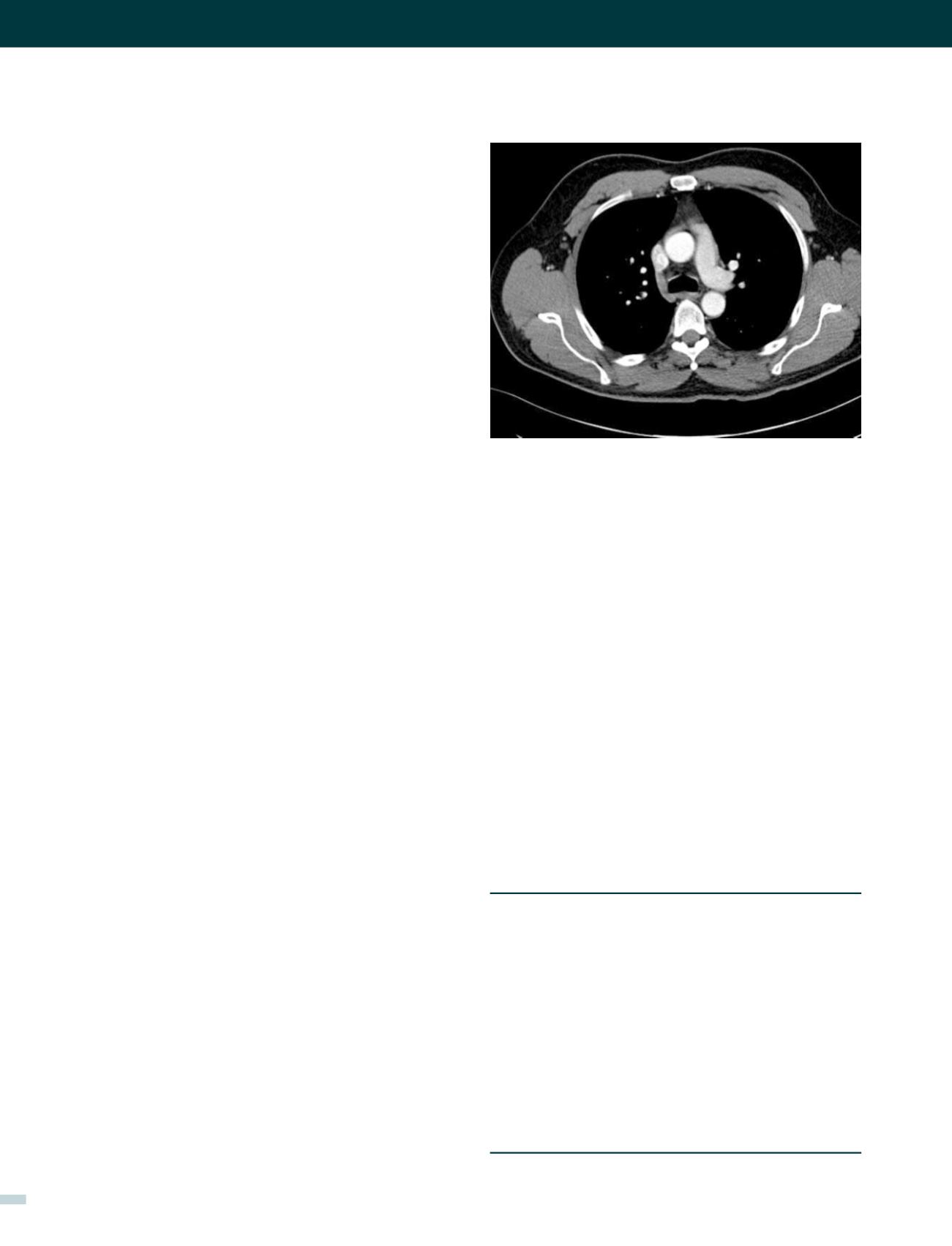

Catheters may be in an obviously incorrect position outside

the vein or appear to follow an approximate normal path on

CXR, but are not correctly sited in the SVC. Axial CT images

show how catheters in the SVC, right pleural space, right

internal mammary vessels, azygous system, ascending

aorta, or mediastinum cannot be distinguished on one

plane imaging (Figure 8). CXR can only confirm central

catheter passage, kinking or procedural complications.

Catheters in an unusual position or malfunctioning need

further investigation before use or removal due to the

risks of thrombosis (CVA) if intra-arterial, pneumothorax,

haemothorax or cardiac tamponade. Bedside tests include;

pressures in all lumens (fluid column or transducer), and

aspiration of blood from the lumens for estimation of

haemoglobin (e.g. systemic blood vs pleural collection),

and oxygen partial pressure. None of these bedside tests

•

Early Arrhythmias Vascular injury Pneumothorax

Haemothorax Cardiac tamponade Neural injury

•

Embolization (including guidewire, catheter, or air).

•

Late Infection Thrombosis Embolization

•

Erosion/perforation of vessels

•

Cardiac tamponade

•

Lymphatic damage

•

Arteriovenous fistula.

TABLE 3. COMPLICATIONS OF CVC INSERTION

are entirely reliable. If in doubt, definitive localisation

requires contrast studies (linogram) or cross-sectional CT

imaging (21). “If in doubt, don’t pull it out! seek specialist

advice.

Complications

Any anatomical structure adjacent or connected to vessels

may be damaged during insertion procedures, or later from

thrombosis, perforation, or infection (Table 3) (22).

Some procedural complications are particularly life-threat-

ening and a frequent cause for high- value legal claims

(23,24). These typically relate to local pressure effects from

an arterial haematoma, massive bleeding into the chest/

abdomen, and strokes from carotid cannulation.

FIGURE 8. AXIAL CT O CHEST

This shows how the internal mammary vessels, medial pleura on right,

SVC. ascending aorta, and azygous vein are all similar in anterior to

posterior plane. Catheters in these different structures cannot be dintin-

guished on one plane imaging (CXR).

[REV. MED. CLIN. CONDES - 2017; 28(5) 701-712]