703

Landmark techniques

Many techniques of accessing the IJV are described (9).

Typical approaches are from the apex of a triangle enclosed

within the two heads of the sternomastoid. The neck is

gently extended and turned a little to the opposite side.

The carotid artery is felt at the level of the cricoid carti-

lage. The jugular venous pulse may be seen, and the vein if

compressed will on release be seen to refill. The needle is

inserted from the apex of the triangle at an angle of o and

aimed towards the ipsilateral nipple. The vein often collapses

under the needle, which then transfixes it, and puncture

is not recognized. The vessel may then be located by aspi-

rating as the needle is slowly withdrawn. The vein is usually

less than 2cm from skin and can be located with a standard

green ‘seeker’ needle. The vein can be cannulated in the

semi-upright position in the case of heart failure or morbid

obesity, if the venous pressure is high.

Ultrasound guidance

There is strong evidence for use of ultrasound for IJV

access to reduce complications and failures (10). Look for

branches (e.g. facial vein), valves, and the carotid, subcla-

vian, and branches thyrocervical trunk. The thyroid gland

(cysts common) and large lymph nodes are visible. Choose

a puncture site and needle direction to minimize overlap of

vein and arteries.

EXTERNAL JUGULAR VEIN

This site is used acutely when a standard peripheral cannula

is placed under direct vision. CVCs passed via the external

jugular vein traverse angles in fascial layers, which may give

problems passing into the subclavian vein.

SUBCLAVIAN VEIN

Landmark approaches are linked with more risks compared

with the IJV, e.g. pneumothorax and incorrect tip place-

ment. It is more comfortable for the patient and a potentially

cleaner site.

Avoid access on the side of arteriovenous fistulae as there is

high pressure in vein and potential risk to fistula from throm-

bosis.

Landmark techniques

The needle is passed under the clavicle at the junction of

its medial third and lateral two-thirds, and then redirected

towards the suprasternal notch, with continuous aspiration

until blood is seen. The vein may be transfixed, so aspiration

is important on needle withdrawal (11).

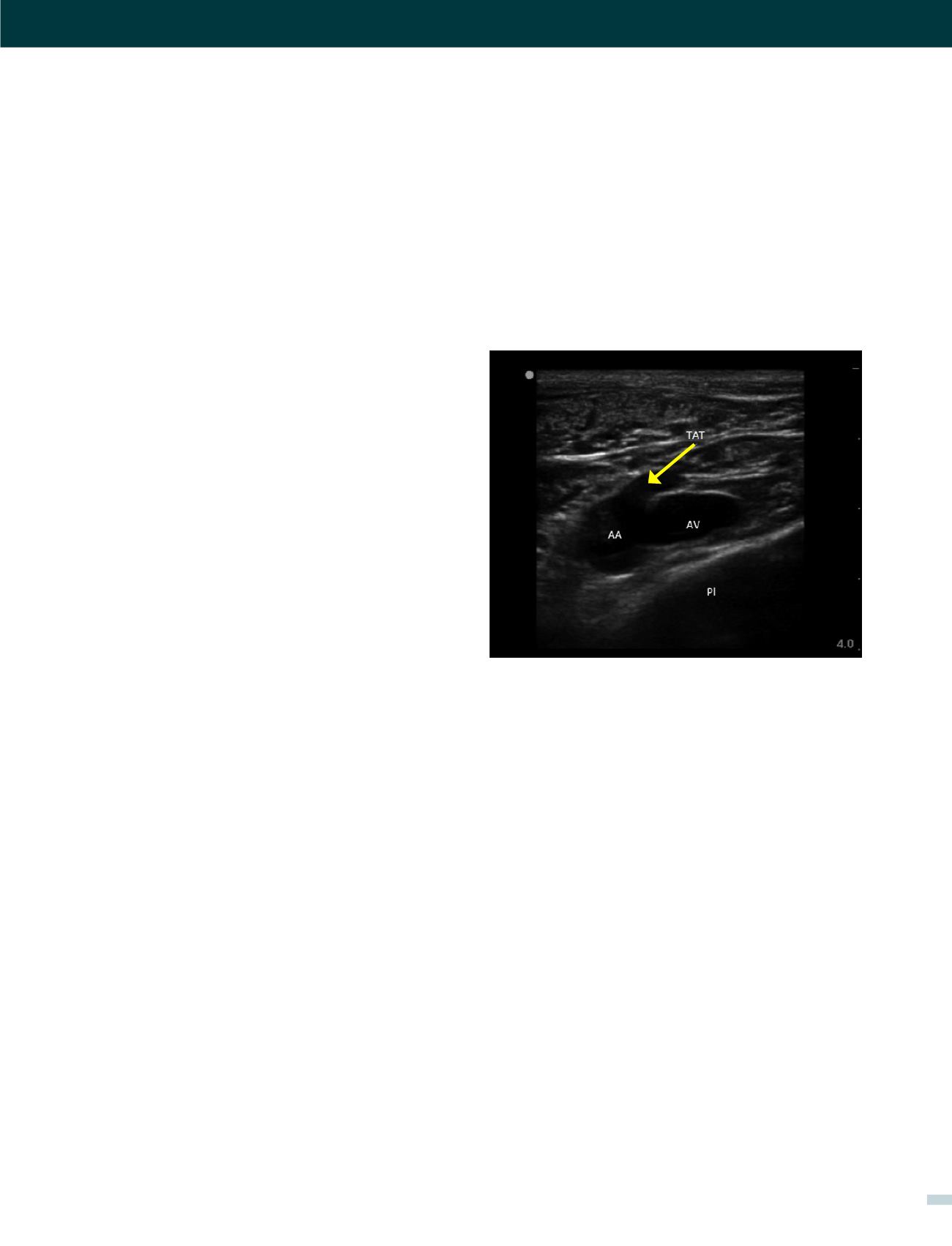

Ultrasound guidance

The clavicle impedes ultrasound, requiring a more lateral

infraclavicular axillary or supraclavicular approach (12).

Recent studies have shown benefits of ultrasound (13,14).

Ultrasound allows avoidance of the nearby pleura, axillary

artery (and the thoracoacromial trunk branches passing

anterior to vein), cephalic vein and brachial plexus (Figure

2). It may be difficult to visualize and access a deep vein in

obese or muscular patients.

FEMORAL VEIN

The anatomy is more complex than the side-to-side orien-

tation of vein and artery in textbooks, which is only relatively

true at the level of the inguinal ligament. Femoral vein access

is useful in patients unable to tolerate head-down position,

in children and emergency situations.

Landmark technique

Palpate the femoral artery and introduce the needle just

medial to the femoral artery close to the inguinal ligament

(not palpable, but represented by a line from iliac crest to

pubis tubercle). It is a common mistake to go too low where

the superficial femoral artery partially overlies the vein.

Ultrasound guidance

Identify the femoral vein and long saphenous vein, and the

common femoral artery dividing into deep and superficial

branches. Higher punctures risk incompressible damage to

vessels, to cause occult bleeding into the peritoneal or retro-

peritoneal space.

[VASCULAR ACCESS - DR. ANDREW BODENHAM]

FIGURE 2. AN ULTRASOUND IMAGE OF RIGHT AXILLARY

VEIN IN MUSCULAR MALE

Note Axillary vein (AV), axillary artery (AA), large thoracoacromial trunk off

axillary artery (TAT), chest wall and pleura (Pl).